As I was reading about the seven types of creative blocks, I couldn’t help but connect them to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. At the base of the pyramid are physiological needs, followed by safety, love and belonging, esteem, and, finally, self-actualization. According to Maslow, it’s challenging to reach higher-level needs, like self-actualization, without first satisfying the more fundamental ones. This concept has significant implications for creativity, as self-actualization is often linked to the ability to express oneself freely and engage in meaningful creative pursuits.

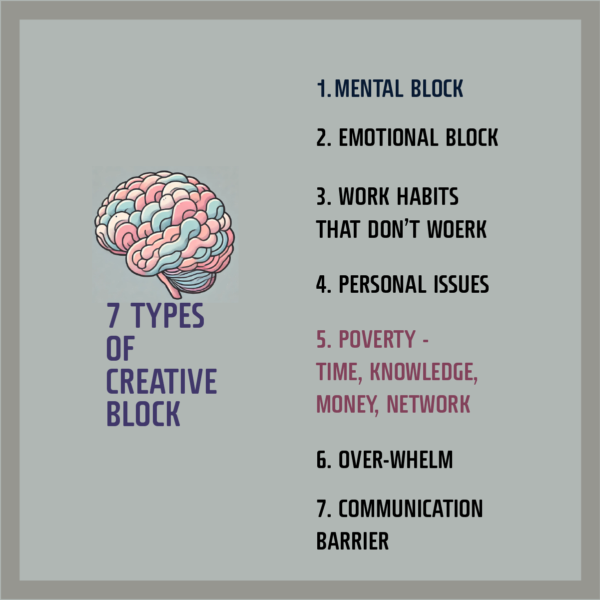

Out of the seven creative blocks[, most seemed quite straightforward. However, the fifth block—‘poverty’—stood out. In this context, ‘poverty’ isn’t solely about financial limitations; it also encompasses a lack of resources, support, or a conducive environment. This led me to question whether creativity, or the ability to engage in creative acts, is ultimately a privilege. It raises the issue of whether creativity is more accessible to those who can afford to nurture it.

It’s important to acknowledge the role of privilege in the creative process. Our upbringing, relationships, and social environment profoundly impact our capacity to express creativity. How much we were encouraged to be different growing up, the extent to which our parents, partners, and friends supported our quirks and ‘weirdness,’ and the quality of our external relationships—all play a part in shaping our creative potential.

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs underscores the idea that basic needs must be addressed before higher-order needs like creativity can be fully realized. When individuals are struggling to meet their physiological, safety, love and belonging, or esteem needs, their creative potential is often suppressed. This is why creative expression can feel inaccessible or unattainable for many.

Research from the University of Southern Denmark supports this view, showing that wealth is a strong predictor of whether an individual pursues a creative profession. For instance, a family income of $100,000 makes it twice as likely that a person will become an artist, compared to someone from a family earning $50,000. This data underscores the systemic barriers that prevent many talented individuals from accessing creative fields, contributing to the historical exclusion of marginalized groups, including women and people of colour, from the art and design world until much later.

Ultimately, this raises thought-provoking questions about how privilege shapes who gets to be seen and heard in creative spaces. Acknowledging privilege doesn’t diminish one’s creativity but rather contextualizes it, helping us understand why some people flourish while others face invisible barriers despite having equal talent or passion.

Recognizing this dynamic invites us to rethink how we create environments that support and nurture creativity in diverse communities. If we want to foster inclusive spaces for artistic expression, we need to address these deeper barriers—economic, social, and structural—that hinder creativity.

It’s a concept that can be explored further, whether in content pieces, discussions, or creative projects, to amplify underrepresented voices and encourage a broader dialogue on what it truly means to cultivate creativity.